Is Noise Pollution the Next Big Public-Health Crisis?

噪音污染会成为下一个大型公共健康危机吗

Research shows that loud sound can have a significant impact on human health, as well as doing devastating damage to ecosystems.

研究表明噪音会对极大地健康人类影响,同时对生态环境造成毁灭性损害。

By David Owen

大卫·欧文

May 6, 2019

2019年5月6日

Noise is now seen as a factor in a range of ailments, including heart disease.

噪音现在被认为是一些列疾病的诱因,其中包括心脏病。

Mark and I sat at opposite ends of a long coffee table, in the living room, and his parents sat on the couch. He took off his earmuffs but didn’t put them away. “I was living in California and working in a noisy restaurant,” he said. “Somebody would drop a plate or do something loud, and I would have a flash of ear pain. I would just kind of think to myself, Wow, that hurt—why was nobody else bothered by that?” Then everything suddenly got much worse. Quiet sounds seemed loud to him, and loud sounds were unendurable. Discomfort from a single incident could last for days. He quit his job and moved back in with his parents. On his flight home, he leaned all the way forward in his seat and covered his ears with his hands.

小马和我坐在客厅长咖啡桌的两端,他的父母则坐在沙发上听我们谈话。他取下了耳罩但并没把耳罩收起来。“我以前住加州,在一个嘈杂的餐厅里工作”,他说,“有人会把盘子掉地上,或者干些别的特别大声的事儿。听到这些我的耳朵就会一跳一跳的疼。我当时想,哇,为什么其他人就不会这么遇到这种烦心事?”之后小马的情况越来越糟。很小的动静对他来说也很大,大一点的噪音他已经完全不能忍受,而且一次声音刺激带来的不适感会持续相当长的时间。之后他辞去工作,搬回父母家。在飞回家的航班上他只能把身体前倾,靠在椅子上,用双手紧紧捂住耳朵。

That was five years ago. Mark’s condition is called hyperacusis. It can be caused by overexposure to loud sounds, although no one knows why some people are more susceptible than others. There is no known cure. Before the onset of his symptoms, Mark lived a life that was noise-filled but similar to those of millions of his contemporaries: garage band, earbuds, crowded bars, concerts. The pain feels like “raw inflammation,” he said, and is accompanied by pressure on his ears and his temples, by tension in the back of his head, and, occasionally, by an especially disturbing form of tinnitus: “You and I would have a conversation, and then after you’d left I’d go upstairs and some phrase you had been saying would repeat over and over in my ear, almost like a song when they have the reverb going.” He manages his condition better than he did five years ago, but he still lives with his parents and doesn’t have a job. The day before my visit, he had winced when his father crumpled a plastic cookie package that he was putting in the recycling bin. By the end of our conversation, which lasted a little more than an hour, he had put his earmuffs back on.

这还只是五年前的情况。小马的症状在医学上叫听觉过敏。过度接触噪音是诱发症状的原因之一(虽然到现在我们还不清楚为什么有的人对噪音比别人更加敏感),而且迄今为止还没有治疗的方法。在小马听觉过敏前,他的生活环境与成千上百万人一样嘈杂,地下乐队啦,热闹酒吧啦,音乐会啦,入耳式耳塞等等。小马形容这个痛觉就像“活生生被火烧”一样,还伴随着太阳穴疼痛、耳压增高、后脑勺紧张等等,偶尔还会引发耳鸣。小马解释,“就好像咱俩刚刚说完话,你先撤了,但是我转身上楼之后你说过的话还在一遍又一遍在我脑子里重放,类似于播曲子的时候加了回声”。现在他的情况已经比五年前好多了,然而现在他仍然与父母住在一起,还找不到工作。就在我采访小马的前一天,他父亲摆放垃圾桶塑料袋的声音仍然让小马难受得龇牙咧嘴。结束这场差不多一个小时的谈话之后,小马又重新带上了他放在桌子上的耳罩。

Hyperacusis is relatively rare, and Mark’s case is severe, but hearing damage and other problems caused by excessively loud sound are increasingly common worldwide. Ears evolved in an acoustic environment that was nothing like the one we live in today. Daniel Fink—a retired California internist, whose own, milder hyperacusis began in a noisy restaurant on New Year’s Eve, 2007, and who is now an anti-noise activist—told me, “Until the industrial revolution, urban dwellers’ sleep was disturbed mostly by the early calls of roosters from back-yard chicken coops or nearby farms.” The first serious sufferers of occupational hearing loss were probably workers who pounded on metal: blacksmiths, church-bell ringers, the people who built the boilers that powered the steam engines that created the modern world. (Audiologists used to refer to a particular high-frequency hearing-loss pattern as a “boilermaker’s notch.”)

听觉过敏其实挺少见的,小马的状况算是严重案例了,但是听力损伤以及其他一些过度接触噪音所造成的疾病却在世界范围内越来越常见。人耳进化历史长河中所处的声音环境与现在我们生活的世界截然不同。丹尼尔芬克是加州的一名退休内科医生,他在2007年跨年夜一个纽约的热闹餐厅里不幸得上了中度听觉过敏。他现在是一名反噪音的积极行动分子:“直到工业革命前,基本上城镇居民每天早上都是被自家后院或者邻居家的公鸡打鸣声吵醒的”。第一批职业性失聪的人群主要和铸铁有关:铁匠、教堂敲钟人以及那些为建设现代世界而制造蒸汽机动力源泉—锅炉的人们。(声学家们一般将高频听力损伤的听力图呈现形式称为“锅炉制造工槽”)

Today, the sound source that people first think of when they think of hearing loss is amplified music, the appeal of which may be biological. In 1999, two scientists at the University of Manchester, in England, conducted an experiment in which they had students listen to songs at dance-club volumes, which are high enough to cause permanent damage if the exposures are long enough. The scientists concluded that the loud music stimulated the parts of the subjects’ inner ears that govern balance and spatial orientation, thereby creating “pleasurable sensations of self-motion”: crank up the volume, and you feel as though you’re dancing when you’re sitting in your seat. Classical musicians and their audiences face risks as well. For the musicians, the threat comes not just from their own instrument (violinists, like right-handed infantrymen, tend to lose hearing on their left side first) but also, often more significant, from the instruments of the musicians who sit behind them.

今天,当人们谈及什么会引起听力损伤时,第一个想到的是经过扩音的音乐。这看起来也很符合生物常理。1999年,两名英国曼彻斯特大学的科学家做了一个实验,他们安排学生听蹦迪舞厅里那么吵的音乐,长期处在这个声音环境中会造成听觉永久损伤。之后他们得出结论称,大音量音乐会调动内耳中控制平衡和空间感的部分,从而制造出一种“自己也在跟着音乐动的、令人愉悦的感觉”:扭大音量,就算坐在椅子上也好像在跳舞。古典音乐家和他们的观众同样面临这种危险。对于他们来说,威胁不仅仅来自于自己的乐器发出的声响(譬如小提琴家,像右撇子步兵一样,左耳更容易损失听力),更多地还来自于他们身旁音乐家乐器的发出的声音。

Modern sound-related health threats extend far beyond music, and they affect more than hearing. Studies have shown that people who live or work in loud environments are particularly susceptible to many alarming problems, including heart disease, high blood pressure, low birth weight, and all the physical, cognitive, and emotional issues that arise from being too distracted to focus on complex tasks and from never getting enough sleep. And the noise that we produce doesn’t harm only us. Scientists have begun to document the effects of human-generated sound on non-humans—effects that can be as devastating as those of more tangible forms of ecological desecration. Les Blomberg, the founder and executive director of the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse, based in Montpelier, Vermont, told me, “What we’re doing to our soundscape is littering it. It’s aural litter—acoustical litter—and, if you could see what you hear, it would look like piles and piles of McDonald’s wrappers, just thrown out the window as we go driving down the road.”

现代社会中与声音相关联的健康威胁不仅仅来源于音乐,所造成的健康后果也不仅仅是听力损伤。研究表明,在大音量环境中工作或生活的人群更容易惹上一些诸如心脏病、高血压、新生儿体重低以及一切认知、行为及情感问题的大麻烦,而这一切都来自于精力分散、无法集中精力完成复杂的工作以及睡眠不足。我们制造的噪音不仅会对人类造成伤害。有科学家已经开始记录人造音对非人生物的影响,这些影响的所造成的破坏性甚至和亵渎生态无异。莱斯·布鲁姆伯格(Les Blomberg)是一所名叫“噪音清除室”(Noise Pollution Clearinghouse)公司的创始人及董事长,该公司位于佛蒙特州的蒙彼利埃。他告诉我说,“我们对声音空间所作所为就是在乱扔垃圾,这是听觉和声学上的乱扔乱放。如果你把声音空间可视化,就能看见像我们开车在路上随手扔出窗外的麦当劳包装纸一样,到处都是一堆一堆的垃圾”。

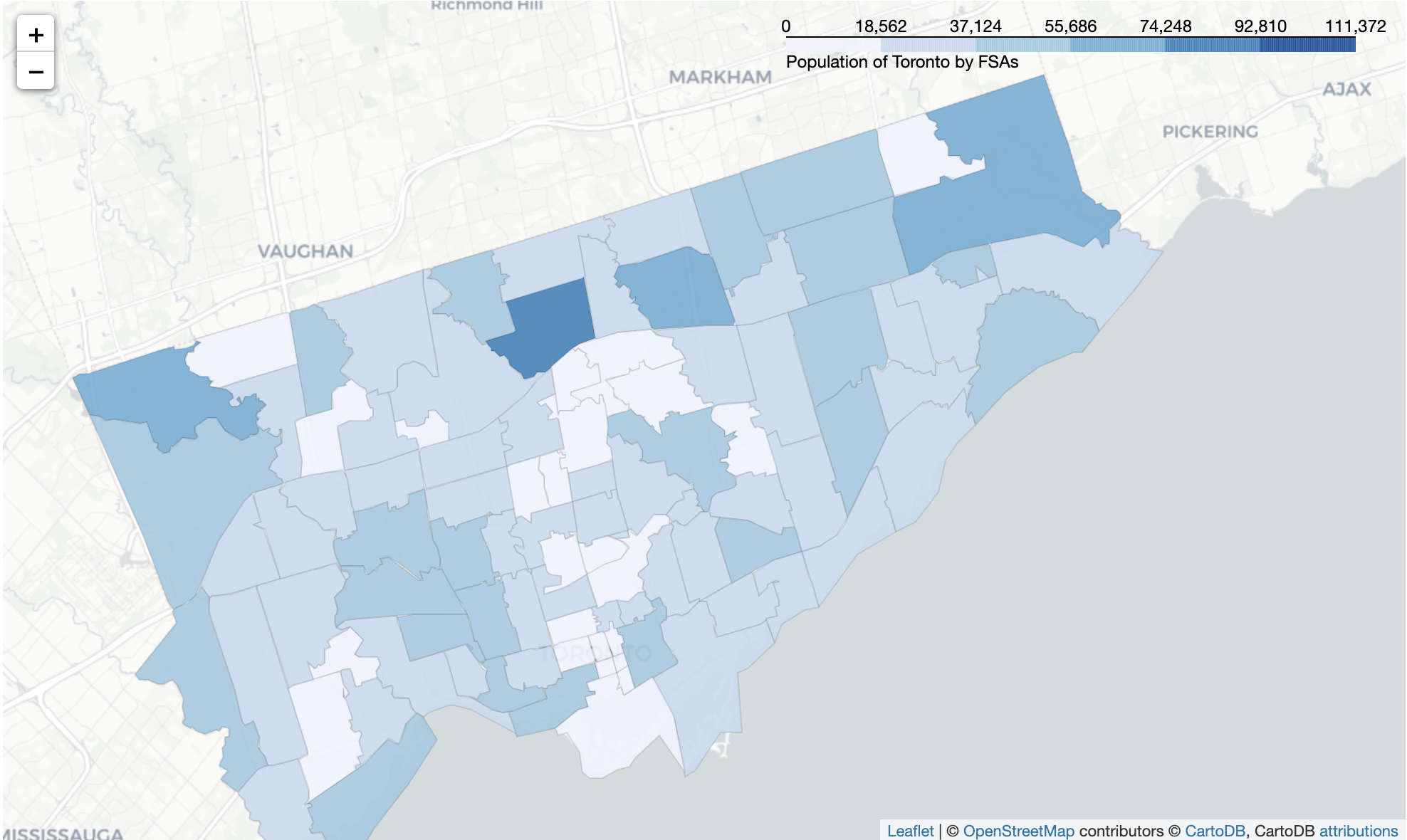

In February, Bruitparif, a nonprofit organization that monitors environmental-noise levels in metropolitan Paris, published a report that combined medical projections from the World Health Organization with “noise maps” based partly on data from its own network of acoustic sensors. It concluded, among many other things, that an average resident of any of the loudest parts of the Île-de-France—which includes Paris and its surrounding suburbs—loses “more than three healthy life-years,” in the course of a lifetime, to some combination of ailments caused or exacerbated by the din of cars, trucks, airplanes, and trains. These health effects, according to guidelines published by the W.H.O.’s European regional office last year, include tinnitus, sleep disturbance, ischemic heart disease, obesity, diabetes, adverse birth outcomes, and cognitive impairment in children. In Western Europe, the guidelines say, traffic noise results in an annual loss of “at least one million healthy years of life.”

今年二月份,Bruitparif,一家位于巴黎城区的声音观察组织发布了一篇报告,它综合运用了世界卫生组织的医学预测以及“噪音地图”,地图部分数据采用的是该组织自身的声音感应器网络。该报告最引人注目的一条结论是,居住在法兰西岛最吵闹地区的居民——包括巴黎及周边一些郊区的行政区域—人均健康寿命将比其他地区的居民减少了至少三年。这主要是由各种汽车、卡车、飞机、火车的轰鸣声所带来的或加重的并发症所导致的。据去年世界卫生组织欧洲区域办事处发布的健康准则,这些健康影响包括耳鸣、睡眠障碍、冠心病、肥胖、糖尿病、不良妊娠结局以及儿童认知性障碍。该准则显示,交通噪音将导致西欧地区人群每年损耗“至少100万健康寿命”。

The headquarters of Bruitparif is in a low-rise office complex in Saint-Denis, a suburb just north of the Eighteenth Arrondissement. I visited a couple of weeks after the February report was issued, and met with Fanny Mietlicki, who has been Bruitparif’s director since 2005. She had warned me, before my trip, that she spoke very little English. I, on the other hand, speak French almost as well as my father did. He studied it in school, and was stationed in France at the end of the Second World War. Years later, at a restaurant in Paris, while travelling with my mother, he said something to a Frenchman sitting at the next table, and the Frenchman said something back. Neither man could understand the other, and my mother eventually identified the problem: the Frenchman didn’t realize that my father was speaking French, and my father didn’t realize that the Frenchman was speaking English.

Bruitparif的总部在巴黎十八区北边圣丹尼斯的一栋矮写字楼里。在他们二月份发布那篇报告之后的几个星期,我去拜访他们了,同时还与芬尼·米耶特利齐(Fanny Mietlicki)见了面。她从2005年起就开始担任Bruitparif的主任了。在我去见她之前,她就警告我说她的英语说的非常不好。我的法语呢,说的差不多和我爸一样好。他当时在学校读书,之后二战中被派往法国驻扎。很多年以后,我爸妈去巴黎玩儿,在餐厅用餐的时候,他对邻桌的法国人说了些什么,之后邻桌又说了些什么回来,而俩人都不明白对方在说些什么。我妈终于明白了问题的出在哪儿:法国人听不出来我爸在说法语,我爸听不出来法国人在说英语。

Mietlicki’s English turned out to be better than she’d let on. “You need to have data in order to know where to implement noise-abatement actions,” she told me. “Before Bruitparif, politicians were fighting to get money to construct noise barriers, but not necessarily where the most people live.” In 2014, Bruitparif was one of the principal creators of the Harmonica index, a way of presenting the severity of sound disturbances with a simple graph. Harmonica’s most appealing feature is that it makes no reference to decibels, which even acousticians have trouble explaining. (Part of the difficulty—but only part—is that decibels are logarithmic. A hundred-decibel sound isn’t twice as intense as a fifty-decibel sound; it’s a hundred thousand times as intense.)

结果米耶特利齐的英语比她描述的要好。她告诉我说,“你得好好整理数据,这样才能明白在哪儿施行消噪措施“。”在Bruitparif成立之前,政客们往往将重点放在争取更多资金来修建噪音屏障上,然而屏障放置的地方却不是大多数人生活的区域“。2014年,Bruitparif成了“悦耳指数”(Harmonica index)的几个主要创始机构之一,该指数用简单的图形展示了噪声的严重程度。悦耳指数最吸引人的一个特点是它并不使用分贝指数来测算噪音,这一点让声学家也很难解释明白。(部分难点,仅仅是部分难点在于——分贝是具有对数性质的。100分贝噪音大小并不是50分贝的两倍,而是成千上百倍的高。)

Bruitparif’s director of technology is Christophe Mietlicki, Fanny’s husband. He used to develop computer systems for financial institutions, but, in 2009, he decided that his wife’s job was more interesting than his, and went to work for her. They are in their forties, have three children, and commute each day from Suresnes, a suburb directly across the Seine from the Bois de Boulogne. At the headquarters, Christophe and I spoke in a sort of reception-and-recreation area on the floor below Fanny’s office. On one of the walls was a large noise map of Paris and its suburbs, on which roads, train lines, and airline flight paths had been highlighted in angry, glowing red, like inflamed nerves in an ad for a pain reliever. On a wooden table in front of the map was a white bowl that was filled with what appeared from a distance to be individually wrapped pieces of candy but turned out to be earplugs.

Bruitparif的技术总监是克里斯托弗·米耶特利齐(Christophe Mietlicki), 芬尼的丈夫。他之前一直为金融机构开发电脑软件来着。然而到了2009年,他觉得妻子的工作比自己的有意思多了,于是辞掉工作来到了妻子的公司。他们俩四十多了,有三个孩子,每天从叙雷讷,一个连接了塞纳河及布洛涅森林的市郊,通勤往返巴黎。我和C克里斯托弗坐在Bruitparif总部一个类似于接待兼休闲区的地方聊天,这个区域就在芬尼办公室楼下。对着我们的一面墙上是一个巴黎及其市郊地区的噪音地图,上面画满了各类公路、铁路以及飞行线路,纵横交错。这些线路图被愤怒的红色线条高亮标记出来,看起来就像是缓解神经疼痛的止疼药广告一般。地图前面摆着一个木头桌子,上边放着一个白碗,远远看上去像是装满了独立包装的糖果,结果凑近一看确是满满一大碗耳塞。

We stepped into an adjacent room. “Here is our acoustic laboratory,” Christophe said. He handed me one of Bruitparif’s sound-monitoring devices, which he had helped invent. It’s called Medusa. It has four microphones, which stick out at various angles, hence the name. The armature that holds the microphones is bolted to a metal box roughly the size of an American loaf of bread. Inside it is a souped-up Raspberry Pi—a tiny, inexpensive computer, which was originally intended for use in schools and developing countries but is so powerful that it has been adopted, all over the world, for myriad other uses. (You can buy one on Amazon for less than forty bucks.) Embedded in the central microphone stalk are two tiny fish-eye cameras, mounted back to back, which record a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree image each minute. Medusas are the successors of Bruitparif’s first-generation sensors, called Sonopodes, which rely on expensive components imported from Japan. Sonopodes are still in use, although they are too big to move around easily. “The Japanese system is very good, but each one costs almost thirty thousand euros, and we can’t deploy it as much as we expect,” Christophe told me. “So we built our own system, which is small and low-cost. The idea is the same.” Bruitparif has installed fifty Medusas in the metropolitan area, and will add many more this summer.

接着我们迈进旁边的一间房子,“这就是我们的声学实验室了。”克里斯托弗说。他递给我一个他们机构的声音监听仪器,他也为开发这个尽了一份力。这个仪器有四个以不同角度向外伸展的麦克风,因此得名美杜莎(Medusa)。支撑麦克风的转子拴在一个像美式吐司一样大的金属盒子上,盒子里装着改良款的树莓派,一个廉价电脑。树莓派原本是供学校以及发展中国家使用的,然而它如此强大,以至于在世界范围内它都在被用来各种改装使用,应用范围极广(你可以在亚马逊上花不到40美金买一个)。中间麦克风的支持杆里嵌入了两个背对背放置的小型鱼眼照相机,每分钟都会录制360度全息影像。美杜莎是Bruitparif第一代声音检测仪Sonopodes的更新款。老一代仪器的部件昂贵,且主要进口自日本。Sonopodes其实现在也在服役,只是太大了,没法灵活移动。“日本的系统非常好用,只是每个都差不多要花3000欧元,我们没法像期望中部署那么多”,克里斯托弗告诉我,“所以我们建造了自己的系统,既小又节省成本,而且原理上也是一样的。”Bruitparif已经在巴黎大都市区安装了50个美杜莎仪器,这个夏天还会安装更多。

In a nearby room, a young woman was assembling Medusa microphones from components that were spread out on a counter. Most of the parts had been 3-D-printed, and she was doing something to some of them with what looked like a soldering iron. “In fact, it’s very simple,” Christophe said. “And, as with many things that are very simple, finding the solution was very complex.” The orientation of the microphones on a Medusa enables it to pinpoint the origins of the sounds that it monitors; the cameras preserve time-stamped images of the scene. Bruitparif can place a Medusa on a street lined with noisy bars and, later, document precisely which bar, at what time, was playing music, say, eleven decibels louder than the local code allows.

邻近的一间屋子里,一位年轻女士正在组装美杜莎的麦克风,柜台上有一些散落的零件。大多数零件都是3D打印出来的,她组装的过程就像是在把零件焊接起来一样。“安装起来其实非常简单”,克里斯托弗告诉我说,“就像很多事儿一样,问题很简单,找到解决方法却很复杂”。美杜莎上的麦克风能准确指向声音的来源,接着相机跟随着方向拍摄,并生成带有时间戳的照片。Bruitparif将美杜莎放置在酒吧一条街,接着记录下来哪个时间、哪个酒吧正在播放超过当地政府规定的,好比说十一分贝的音乐。

I said that documentation like that would be useful in New York, where the police often ignore noise complaints or respond to them days later.

我说这个记录在纽约实在是太有用了,警察经常忽略噪音投诉或者隔了很久才有反应。

“The idea of this system is not to depend on the police,” Christophe said. “That should be the last resort. We prefer a system in which people like you, like me, can put a sensor somewhere and have objective data, and then we can talk with one another and find some solution together.”

“其实这个系统本意上是不依靠警察来处理的”,克里斯托弗说,“找警察来处理噪音其实应该是我们最后的手段了。我们希望创造一个系统,像咱们一样的人能把这个检测仪放在什么地方以记录客观数据,接着我们能和其他人谈谈,一起想出解决方案来”。

Ah, mais oui. (But the data would probably also stand up in court.)

啊哈,但是。。(但是这些数据也很有可能在法庭上站得住脚。)

A few weeks later, back in the States, I visited the headquarters of a smaller but similar noise-monitoring project, at N.Y.U.’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, on Jay Street, in Brooklyn. That project is called Sounds of New York City (SONYC) and is funded mainly by the National Science Foundation. SONYC’s purpose, Mark Cartwright, one of the scientists on the project, told me, is “to monitor, analyze, and mitigate noise pollution.” Each sensor in its network has just one microphone, which is roughly eight inches long and covered in foam. The microphone is attached to a small, weatherproof aluminum box, which also contains a Raspberry Pi. Sometimes the sensors are mounted with a long strip of plastic spikes, which are meant to deter pigeons from using the devices as latrines, and which, on monitors installed near Washington Square Park, have developed the unanticipated additional function of accumulating tangled masses of the wind-borne hair of N.Y.U. students.

过了几周我回到美国,拜访了纽约大学城市科学与进步中心的噪音监控项目总部,它位于布鲁克林杰伊街。这个项目与上文中法国的类似,只是规模上略小。项目名为“纽约市之声(Sounds of New York City (SONYC))”,主要由美国国家科学基金会赞助。马克·卡特莱特(Mark Cartwright)是这个项目的科学家之一,他告诉我说,纽约市之声的主要目标是“监测,分析,并缓解噪音污染”。他们也有自己的探测器网络,每个网络中的探测器有一个大约8英尺长、用泡沫包裹住的麦克风,连接着一个不受天气影响的小型铝制盒子,盒子里也装着树莓派。这些探测器有时候也用长长的塑料刺状物包裹着,这样可以防止仪器被鸽子们当洗手间使用。另外,有些安装在华盛顿广场公园的检测器还发挥了大家没想到的作用——收集了大量缠绕着的、被风吹起来的纽约大学学生们的头发。

The method that SONYC uses to collect data and to document noise-code violations is different from the one used by Bruitparif. The SONYC researchers are developing algorithms that they hope will eventually be able to identify a full range of noise sources by themselves—an example of so-called machine listening. “Having a network of sensors deployed around the city enables us to start understanding the patterns of noise and how they develop around things like construction sites,” Charlie Mydlarz, another scientist on the project, told me. He said that SONYC also gives the city’s Department of Environmental Protection actionable evidence of violations. Mydlarz and his colleagues are still training their algorithm, with help from “citizen scientists,” who visit a Web page and annotate ten-second audio files, collected by the sensors, with what they think are the sounds’ likeliest sources: jackhammer, car alarm, chainsaw, engine of uncertain size. He demonstrated the algorithm’s current iteration by alternately operating a Black & Decker electric drill and the siren of a toy fire truck near a sensor on the table in front of him. The algorithm successfully identified each and measured its decibel level. (It can also identify the fire truck’s horn.)

纽约市之声用来收集数据以及记录违反噪音管制条令的方式与Bruitparif不同。纽约市之声的研究者们正在研究一种最终能在全范围自行探测出噪声源的算法——这也是机器学习应用的一个范例。另外一位负责该项目的科学家查理·麦德拉兹(Charlie Mydlarz)告诉我,“在全市范围内部署探测仪网络能让我们了解到噪音的模式是怎么样的,以及这个模式在建筑工地附近呈现的态势”。他说,纽约市之声已经能为纽约市环境保护机构提供可供定案的证据。麦德拉兹和他的同事们仍然在训练这个算法,他们也获得了“公民科学家”们的帮助,热心民众们访问这个项目网站并协助科学家们将探测器收集到十秒长的声音文件加上注解。他们通过辨别声音类型来帮助项目将噪音分类:电钻、车辆报警器、电锯以及某种未知大小的机器引擎声等等。麦德拉兹为了向我展示项目的算法迭代成果,在检测器旁分别打开了一个百德钻孔机和一个玩具卡车的警铃。结果算法成功的分辨出了两种声音的名称,并测量了声音的分贝等级。(它同样能分辨消防车的喇叭声。)

I was accompanied to the SONYC lab by Charles Komanoff, an economist who created models that the city’s congestion-pricing plan is based on. In the course of the past five decades, he’s worked on just about every environmental issue, including noise. “In the mid-nineties, I spoke fairly regularly to small but spirited anti-car gatherings,” he told me. “I would ask for a show of hands: ‘If you could eliminate all motor-vehicle noise or all motor-vehicle air pollution—but not both—which would you choose?’ As a rule, the majority chose noise.” I had asked him to join me mainly because he owns a professional sound-level meter.

查尔斯·克曼诺夫(Charles Komanoff)陪我参观了纽约市之声的实验室。查尔斯·克曼诺夫一名经济学家,构造了一些被纽约市政府用来计算交通堵塞费用的模型。在过去的五十年时间里,他一直在研究差不多每一个环境问题,包括噪音。“九十年代中期的时候,我经常给一小群富有激情的反对车辆的人群演讲”,他告诉我,“我会让他们举手表决:‘如果你们能解决所有的汽车噪声问题或者汽车污染,但是只能解决一个问题,你们会选哪一个?’一般来说,大多数人都会选择解决汽车噪声”。其实我叫他过来主要是他有一块专业的声级计。

Komanoff and I travelled to and from Brooklyn by bicycle, and halfway across the Manhattan Bridge we stopped to take sound readings. His meter showed that, at the spot where we were standing, the average ambient-sound level, arising mostly from motor traffic on the bridge, was about seventy decibels, or roughly what you’d experience while using a vacuum cleaner at home. Then a train went over the bridge, on tracks twenty or thirty feet from where we were standing, and the reading jumped to ninety-five decibels—more than a three-hundredfold increase in sound intensity and a five- to sixfold increase in perceived loudness—or roughly what you’d hear while using a gasoline-powered lawnmower in your yard. The train sound wasn’t physically painful, but almost; even shouted conversation became impossible.

克曼诺夫和我蹬着自行车往返布鲁克林,在半路上我们停在曼哈顿桥上来测量声级计读数,上面显示就在我们站的这个地方,平均环境音量达到了70分贝。这些声音主要来自于桥上的过往汽车交通声,差不多和在家用吸尘器的声音一样大了。过了一会儿一辆列车经过大桥,离我们站的路差不多20-30尺吧,接下来平均环境音量蹿到了95分贝——这差不多是300倍音强,5-6倍的体感响度——或者就像你家后院里汽油式除草机工作的声音。列车声听起来并不刺耳和痛苦,但是在这种环境下两人大声吼叫着来谈话互相也听不见。

In the United States, sound exposure in the workplace has been regulated by the federal government since the nineteen-seventies. But the rules don’t cover all industries, and they’re applied inconsistently. The government has acknowledged that, even when compliance is absolute, the limits aren’t low enough to protect all workers from hearing loss. The regulations of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, for example, allow workers to be exposed to ninety-five decibels for four hours a day, five days a week, for an entire forty-year career. That’s always been crazy, but in the past decade it’s begun to seem even crazier, because recent research into what’s known as hidden hearing loss—which involves a previously undetected permanent reduction in neural response—has suggested that catastrophic losses could occur at sound levels that are much lower than had been thought, and after much shorter periods of exposure.

在美国,工作场所的声音暴露量从19世纪起就受联邦政府的监管。但是这些规则并不适用于所有行业,规则也有的时候也流于形式。政府自己也承认,即使合规审查到位,声音暴露量的限制也达不到保护所有员工远离听觉损失的程度。比如,美国职业安全与健康管理局法允许员工在四十年工作时长中,每周五个工作日内,每天暴露在95分贝的工作环境里四个小时。这简直是疯了,然而过去的十年情况却变得越来越疯狂。最近一项关于隐性听觉障碍——与永久性神经反应损伤有关——的调查表明,灾难性的听觉损伤很有可能发生在比我们预期中低得多的声音水平、短得多的暴露时间里。

By the mid-nineties, some scientists had begun to believe that traffic noise must be harmful to creatures other than humans, but they didn’t know how to measure its effects in isolation from those of roadway construction, vehicle emissions, highway salting, and all the other direct and indirect ecosystem insults that arise from our dependency on cars and trucks.

九十年代中期,一些科学家开始认为交通噪音不仅对人类有害,还对其他生物有负面影响。然而他们无法隔离测量铁路建设、汽车尾气、高速公路盐污染以及其他一些人类依赖汽车及卡车导致的,直接或间接的对生态环境的冒犯。

In 2012, Jesse Barber, a professor at Boise State University, in Idaho, thought of a way. He and a group of researchers built a half-kilometre-long “phantom road” in a wilderness area where no real road had ever existed. They mounted fifteen pairs of bullhorn-like loudspeakers on the trunks of Douglas-fir trees, and, during bird migration in autumn, played recordings of traffic that Barber had made on Going-to-the-Sun Road, in Glacier National Park. Chris McClure, who worked on the project, told me, “We cut up garden hoses to run the wires through, so that mice wouldn’t chew on them, and we duct-taped pieces of shower curtains over the loudspeakers, to keep off the rain.” The recorded sound wasn’t deafening, by any measure; to a New Yorker, in fact, it might have seemed almost soothing. But its effect on migrating birds was both immediate and dramatic. During periods when the speakers were switched on, the number of birds declined, on average, by twenty-eight per cent, and several species fled the area entirely. Some of the biggest impacts were on species that stayed. Heidi Ware Carlisle, who earned her master’s degree for work that she did on the project, told me, “If you just counted MacGillivray’s warblers, for example, you might say, ‘Oh, they’re not bothered by noise.’ But when we weighed them we found that they were no longer getting fatter—as they should have been, because fat fuels their migration.”

2012年,美国爱达荷树城州立大学的教授杰西·巴伯(Jesse Barber)提出了一个解决方案。他和一群研究员在荒郊野外建了一条半公里长的“幽灵路”,这个地方从来没有真正的路过。接下来,他们在周围黄杉树的树墩上安装了15对扩音大喇叭,在鸟类迁徙的秋天,播放他的车在冰川国家公园知名公路——奔向太阳之路奔驰所记录下来的交通录音。克里斯·麦可鲁尔(Chris McClure)也是项目研究者之一,他告诉我说,他们为了做实验,“切断了花园的水管来穿电线,这样老鼠就不会咬他们了。我们还用橡胶条把浴帘布碎片包到扩音器上,防止扩音器被雨淋湿。”其实录音的内容一点也谈不上震耳欲聋,对于纽约人来说听起来可能还有颇为舒心。然而这些声音对迁徙的鸟类带来的后果既直接又显著。喇叭开着的这段时间里,鸟类数量平均减少了28%;还有几种鸟完全飞离了这个区域。有些巨大的影响体现在留在这个区域的鸟类身上。海蒂·瓦雷·卡莱尔(Heidi Ware Carlisle)在这个项目上的付出为她赢得了硕士学位。她告诉我,“打个比方,如果你数数灰头地莺的数量,你会说‘噢,他们也没受噪音的影响嘛”’。然而当我们给他们称体重的时候发现,他们并没有变重。他们应该得变重让脂肪提供足够的能量帮助他们渡过迁徙季。”

A dozen years before the phantom-road experiment, a group of American researchers accidentally performed a similar study underwater. They had been measuring concentrations of stress-related hormone metabolites in the feces of right whales in the Bay of Fundy. (They were assisted by dogs trained to detect the scent of whale turds from the side of a boat.) In mid-September, 2001, the metabolite concentrations fell; when they were measured again the following season, they had gone back up. The scientists had been using hydrophones to monitor underwater sound levels in the bay, and they realized that the drop in stress had coincided exactly with an equally sudden decline in human-generated underwater noise. The cause was the temporary pause in ocean shipping which followed 9/11.

幽灵路实验的十二年前,一群美国研究员无意间在水下做了一个类似的实验。他们一直在加拿大芬迪湾研究露脊鲸粪便中与压力相关的激素代谢物的浓度。(他们在受训犬只的帮助下在船的两侧寻找鲸鱼粪便的气味。)在2001年的9月中旬,他们发现代谢物浓度下降了;同年冬天他们再次测量之后发现,这个压力值又回来了。科学家们在芬迪湾用水听器监测水底声音强度之后发现,鲸鱼压力值下降的同期,人类在水下产生的噪声也突然降低了。这是因为911事件之后,海洋运输暂时停止了的缘故。

I learned about the Bay of Fundy project from Peter Tyack, an American behavioral ecologist, who, for the past seven years, has been a member of the faculty at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland. He also does research at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, on Cape Cod, where he used to work full time—and that’s where we met. We sat in a lab on the second floor of W.H.O.I.’s Marine Research Facility, and he explained that sound can harm marine creatures both directly, by physically injuring them, and indirectly, by interfering with their feeding, their mating, and their communication. “We’re visual creatures, but sea animals don’t need to be,” he said. “Underwater, you can see maybe ten metres, but you can hear things a thousand kilometres away.” The loudest human sounds in the oceans are made by seismic air guns, which are used to search for undersea deposits of oil and natural gas. (They’re so loud that acoustic monitors on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge pick them up from hundreds, and even thousands, of miles away.) “In terms of the total sound energy that humans put into the ocean, though, shipping is by far the biggest source,” he said.Tyack gave me a tour of the research facility downstairs. We passed a bank of freezers, a room with a CT scanner, and a band saw big enough to carve a small whale into chunks, and then entered a room that was furnished with supersized versions of the kind of stainless-steel tables you’d find in the autopsy room of a morgue. “There’s a big door over there, so that a truck can back right up,” he said. “And those gantries up on the ceiling move the animals onto the tables.”

我是从美国行为生态学家皮特·泰雅克(Peter Tyack)那儿知道芬迪湾的项目的。他在过去的七年里一直担任苏格兰圣安德鲁斯大学的教师,同时也在位于美国鳕鱼角的伍兹霍尔研究所从事研究工作,我们就是在这儿见面的。我们俩坐在研究所二层的海洋实验室里,他跟我解释声音是如何直接地、生理上损害海洋生物的同时又间接地影响到他们的摄食、交配以及沟通的。“我们是视觉生物,但是海洋动物可不需要视觉”,他说,“在水底,你可能能看到10米的距离,但是能听到1000公里外的动静。”海洋里最吵的人造声是由海洋地震气枪发出的,这个主要用来探寻海底石油及天然气储量。(这个声音大到上百英里、甚至是上千英里外的大西洋中脊声波探测器都能捕捉到。)“然而,至今为止,人类在海洋里投放的最大声能却来源于航运。”他说。泰雅克带我去楼下的实验室里逛了一圈。我们经过了一排排冰柜,一个放着CT机的房间,以及一个大到足以把小鲸鱼切成块儿的带锯。接着我们走进一个由一些超大型停尸房解剖间里的那种不锈钢大桌子装潢的房间。“在这儿后面有个大门,卡车能在后面直接停下来”,他解释说,“之后屋顶的龙门架就能把动物们直接挪到桌子上。”

One of Tyack’s ongoing research interests is the impact of sonar on marine mammals. He and his colleagues have developed a sound-and-movement monitor—“sort of a waterproof iPhone”—which they can affix, with suction cups, to whales’ backs. They have discovered, among other things, that some species are more sensitive to sonar than anyone had previously suspected. “If they hear sonar, they’ll stop foraging, leave the area, and not come back for several days,” he said. Sometimes frightened whales bolt toward the surface and die of decompression sickness—the bends—or of an arterial gas embolism. He continued, “We are now quite sure that what happens is that the whales are a kilometre deep, and they’re foraging in the dark for food, and the sound of sonar from a naval exercise triggers a panic reaction.”

泰雅克现阶段的一个研究兴趣在声纳对海洋动物的影响。他和同事们开发了一个声音-动态检测仪,按T泰雅克的话说,有点像个防水的iPhone。他们能将这个仪器用吸盘吸附在鲸鱼的背上。他们在众多结果中发现,有些鲸鱼种类对声纳的敏感程度超出之前研究者的预料。“他们听到声纳后会停止觅食,离开这片区域,在接下来的几天时间内也不会回来,”,泰雅克说。有的时候受惊的鲸鱼会冲上海面,并死于潜水夫病这样的减压症或动脉空气栓塞。泰雅克继续向我解释,“有关与鲸鱼的遭遇,我们现在非常明白的是,他们当时在水下1km深度的黑暗水域里觅食,海洋实验所发出的声纳声导致了他们恐慌症发作。“

Tyack said that it’s long been known that human-created sound can also interfere with mating calls, thereby reducing the reproductive success of many species, including ones that have already been hunted virtually to nonexistence. Consequent reductions in those species’ numbers can be invisible even to marine biologists, since the failure to reproduce doesn’t result in carcasses on beaches. “Even now, our estimates of the population size of marine mammals are plus or minus fifty per cent,” he said. “So, basically, the population would have to be on its way toward extinction before we’d notice. And by then it would be too late.”

泰雅克说,人们很早就知道人造声会干扰海洋生物的求偶鸣叫,因此减少了许多海洋生物的繁殖成功率,其中包括一些被追猎得濒临灭绝的种类。这些生物大量减少的情况对于甚至是海洋生物学者来说都是无法观测的,因为他们繁殖不成功并不会导致海滩上出现神秘海洋生物尸体。“直到现在,我们对海洋生物群体大小的估计值浮动区间是正负50%”,他说,“所以基本上来说,等我们能发现异常情况的时候这种生物都快灭绝了。到这个时候就实在太晚了。”

On the day that Charles Komanoff and I took those sound readings on the Manhattan Bridge, I also visited Arline Bronzaft, a retired professor of environmental psychology, at her apartment, on East Seventy-ninth Street, near the river. In 1975, she and a co-author published an influential research paper that, like the phantom-road and whale-poop studies, hinged on an accidental discovery. “One of my students, at Lehman College, told me that her child attended an elementary school next to an elevated train line, and that the classroom was so loud that the students were unable to learn,” she said. The school was P.S. 98, in Inwood, near the northern tip of Manhattan, and the track was two hundred and twenty feet from the building. Bronzaft’s student said that she and some other parents were planning to sue, but Bronzaft, whose husband was a lawyer, told her that, in order to be successful, they would need to prove that their children had been harmed. Bronzaft offered to help and found that, in classrooms on the side of the building facing the tracks, passing trains raised decibel readings to rock-concert levels for roughly thirty seconds every four and a half minutes, and that, during those periods, teachers had to either stop teaching or shout; then, once a train had passed, they had to regain their students’ attention.

Bronzaft obtained three years’ worth of reading-test scores from the school’s principal—“I must say, he was an activist principal,” she said—and was able to demonstrate to the city that the sixth graders on the track side of the building had fallen about eleven months behind those on the quieter side.

我和查尔斯·克曼诺夫骑车去曼哈顿桥测声音读数的那天,还去拜访了艾琳·彭萨福特(Arline Bronzaft),一位退休的环境心理学教授,她家住在哈德逊河附近的东79街。1975年她和人联合发表了一篇颇具影响力的论文。这个研究和“幽灵路”以及“鲸鱼便”一样,实验也是在不经意中完成的。“一位我曾在纽约州立大学莱曼学院(Lehman College)教过的学生告诉我说,她的孩子在铁路旁的一所小学读书。每天教室噪音太大了,学生们根本没法读书。”艾琳·彭萨福特告诉我说。这个学校叫P.S. 98,,就在北曼哈顿顶端的英伍德。列车轨道离学校教学楼差不多220英尺远。彭萨福特的学生说她和其他一些学生家长本来打算起诉,但是她的丈夫,一名律师告诉她,要想赢官司,他们得证明孩子们的确受到了伤害。彭萨福特站了出来。她发现,教室里面对轨道的那一侧,来往的列车每四分半钟能将分贝读数提高到摇滚音乐会的等级。在此期间,老师们要么暂停课堂要么只能大吼大叫地继续上课。等列车经过之后,老师只能重新花时间让学生们集中精力上课。彭萨福特从校长那儿拿到了差不多学生们三年的阅读课成绩——“我必须得说,校长他的确是一名行动派”,她说。总之她能证明教学楼里靠近轨道的六年级学生成绩比教学楼安静部分学生的课堂进度少了11个月。

Bronzaft stayed involved. She helped persuade the city to cover the classroom ceilings with sound-deadening acoustic tiles, and the M.T.A. to install rubber pads between the rails and the ties on tracks near the school (and, eventually, throughout the subway system). In a follow-up study, published in 1981, she was able to show that those measures had been effective and that the gap in test scores between students on the exposed and less exposed sides of the building had disappeared.

彭萨福特并没有停止脚步。接下来她敦促市里将教室内装上了消音瓷砖,并且让纽约大都会运输署在学校附近的列车轨道和轨枕上装上了橡胶垫(最终整个铁路系统都用上了这一招)。她的下一项研究结果于1981年发表,证明了以上这些消音措施都卓有成效,暴露在列车噪音学生们与那些身处教学楼较安静部分学生的进度差距已经消失了。

Those experiences increased Bronzaft’s impatience with scientists and politicians who hesitate to act on persuasive but incomplete data. She asked me if I knew who had been the President of the United States at the time of the passage of the federal Noise Control Act and of the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. And I did know: Richard Nixon. She took me into her office, a book-filled study that she calls the Noise Room, and, on a couch, opened an accordion folder that contained a dozen or so U.S.-government pamphlets, most of them from the seventies. One described noise impacts identical to the ones that researchers all over the world still study today, including hearing loss, cardiovascular disease, interrupted sleep, and delayed reading and language development.

彭萨福特的种种经历增进了她对那些拿着她不太完整却极有说服力的数据,却迟疑不前、不采取措施的政客以及科学家的不耐烦感。她问我知不知道是谁通过了美国联邦噪音控制法、成立了国家环境保护局、职业安全与健康管理局与国家职业安全卫生研究所。我的确知道是谁:理查德尼克松(Richard Nixon)。她领着我走进他的办公室,她自己称为噪音室,一间堆满了书的书房。房间里放着一个沙发,上面摆着着一个打开的文件资料包,里面装了差不多一打70年代美国政府印刷的小册子。其中一本册子关于噪音影响的描述与今天世界范围内研究者的结论一样:噪音将造成包括听觉损伤、心脑血管疾病、睡眠失调、阅读以及语言障碍在内的一系列问题。

It concluded with a quotation from William H. Stewart, who served as the Surgeon General under both Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon. In his keynote address at the 1968 Conference on Noise as a Public Health Hazard, in Washington, Stewart said, “Must we wait until we prove every link in the chain of causation?” and added, “In protecting health, absolute proof comes late. To wait for it is to invite disaster or to prolong suffering unnecessarily.”

最终这个小册子以曾经担任过林登·B·约翰逊(Lyndon B. Johnson)和尼克松(Nixon)的医务总监威廉·H·斯图尔特(William H. Stewart)的一句话作为结尾。1968年他曾在一个主题为“噪音——公共健康危害“的大会上做主旨演讲,他说,“我们一定要等到能证明每一条因果关系链都合理的那一天吗?”以及“在健康防护领域,要等到获得事实证据的那一天就太晚了。等待意味着我们邀请灾难进家门或者毫无理由的延长人们忍受痛苦的时间。”

That was half a century ago. Scientists still don’t know everything there is to know about the effects of sound on living things, but they know a lot, and for a long time they’ve also known how to make the world substantially less noisy. Peter Tyack told me that reducing the sound impact of global shipping would be possible, since “the navies of the world have spent billions of dollars learning how to make ships quiet.” One method, he said, is to physically isolate engines from metal hulls; another is to shape propellers in ways that make them less likely to produce shock waves in the water. Subway cars everywhere could roll on rubber tires, as some of the ones I rode in Paris do. Highway speed limits could be enforced; so could laws requiring the use of E.P.A.-approved exhaust systems on all motorcycles. Maximum earbud volumes could be limited to indisputably safe levels. Directional sirens could significantly reduce or eliminate noise for people who are not in the path of an emergency vehicle. Measuring noise is important, Bronzaft said, but it isn’t an end in itself. “If I don’t see the data being used to get action, I’m not going to be happy,” she continued. “We had all this stuff in the nineteen-seventies. And what have we done?”

这都已经是半个世纪之前的事了。科学家们现在仍然不能说明白声音对生物的每一种影响到底有什么,但是他们非常清楚并且长久以来了熟于心的是,如何才能让这个世界安静下来。皮特·泰雅克告诉我说,现在减少国际航运所造成的声音影响是有可能的,因为“海洋国家们为了让船只更加安静已经花费了几十亿美元。”他说,其中有一种方法是从物理结构上入手的,那就是将引擎与金属船体分离开来。另外一种是重塑螺旋桨的外观,这样能减少船只在水中产生震波的可能性;四处可见的地铁列车可以像我当时在巴黎搭乘的地铁那样,换上橡胶轮胎;高速公路速度应该被限制;法律还可以从美国环保局排气检测入手,对每一辆机动车进行检测;入耳式耳塞的最大音量应该被设计在无可争辩的安全级别以下;声音方向可控的警报器也能大大减少或者消除不在紧急车辆道路上人们所接收的噪音。噪音检测很重要,彭萨福特补充说,但是不应该检测完就没下文了。“我要是看不到这些数据被好好利用起来,我可不会开心的。”她接着说,“我们在70年代就有这些噪音检测的玩意儿了。我们这些年采取什么措施了吗?”